Unsentimental brickwork

04.09.2017The non-bearing brick-faced façade wall has prevailed and today we miss the structural logic that helped give the masonry of the past its rich expression. By following the structural rules of the brick-faced façade – can we give the masonry of today a richness in expression that can match the past? For Gottlieb Paludan Architects, this has long been a central, professional challenge.

How do you conceive expert ideas as to how to achieve a similar richness of architectural expression found in earlier Danish and North European masonry traditions? Genuinely contemporary architecture should react to the fact that it is rare for modern brickwork to be structurally load-bearing.

The building industry has used facings since the 1920s. The oil crisis of 1973 definitively established the division of the walls in a load-bearing inner leaf and a non-bearing outer leaf. Though connected by wire ties, they live quite separate lives. The inner leaf has become the preserve of the concrete industry. For the outer leaf - at least in a Danish context - bricks are favoured by virtue of its unique role in the country’s building traditions.

A stepping stone to the context

Creative Director Jesper Gottlieb explains: ‘We use bricks as a means of connecting a building to a context where bricks are already present. In addition, many of the small technical plants that we are working with are closed and inward-looking. This makes bricks an obvious material in contrast to, for instance, glass.’

He also points to how the small modular unit size of bricks can achieve a monolithic appearance. However, it is worth bearing in mind that bricks are no panacea. A case in point is the CHP plant Svanemølleværket in Copenhagen which is a brick structure of enormous proportions. It does pose the question just how many bricks it is actually reasonable to transport and stack on top of each other.

,,

These additional buildings in their brick overcoats look quite similar but sport small subtle differences. They are clearly modern but register with an industry atmosphere stemming from the utilities architecture of earlier decades

Thomas Bo Jensen is a professor at the Aarhus School of Architecture. Among an extensive academic body of work on brickwork, he is the author of - a PhD thesis entitled The Ornamental Will of Bricks which has become a reference work on the tectonics, building culture and architectural potential of brickwork. Jensen refers to Gottlieb Paludan Architects’ recent brick-faced constructions as the beginning of a new layer of familiarity in the city:

‘These additional buildings in their brick overcoats look quite similar but sport small subtle differences. They are clearly modern but register with an industry atmosphere stemming from the utilities architecture of earlier decades. In this way, they create a layer of identity in the Copenhagen cityscape. It is one layer among many, but one which is more concerned about continuity than merely adding another novelty.’

He highlights a German example of this way of working: for a number of years from the 1920s onwards, the architect Hans Heinrich Mller designed more than fifty brick utilities buildings for the electricity company Bewag in Berlin. There are both small and large structures, all of excellent quality. The 35–40 surviving buildings are still today recognizable across the different neighbourhoods of the city. ‘This is what the physical manifestations of infrastructure can contribute: creating connections across the city,’ explains Jensen.

The brick facing challenge

The facing bricks in the outer leaf behave differently under thermic changes than the concrete of the inner load-bearing leaf. This makes it necessary to divide the facing into sections with the aid of so-called expansion joints (movement joints).

This requirement has become acute, as these days, the majority of brickwork is laid in hard cement mortar. This means that if the facing is stressed beyond its flexibility, cracks are more likely to appear in the bricks themselves rather than in the joints - as one would intuitively expect.

In many ways, Jensen is critical of the ubiquitous use of brick facings. However, he does see potential in treating brick facings as an architectural motif in its own right. This may involve prefabrication, “collage strategies” with regards to the sectioning of the brickwork or taking up the necessary expansion joint as a design challenge. Paradoxically, it may be turned into an artistic quality via, for example, recesses and bond changes.

,,

Classifying materials as good/bad or dated/contemporary makes, quite simply, no sense to me

Architect MAA Adam Wingstrand has taken part in several of Gottlieb Paludan Architects’ projects employing textured brickwork. He emphasizes that one should not underestimate the significance of the bond! A seemingly trite observation: “innocuous” details on a drawing make a huge difference to the way a building will appear in its proper context.

Wingstrand explains: ‘When building solid brickwork, you will have to turn some of the bricks in order to obtain an interconnected weave. This means that the headers (the short sides or “gable ends” of the brick) will show directly in the façade. In a cavity wall, the outer leaf is only half a brick wide. Personally, I think that it is a little silly to choose bonds with headers in an ordinary facing. In this case, the bricklayer will have to cut a number of the bricks in half in order to get the pattern to fit. The stretcher bond (where the long sides of the bricks show) has a poor reputation in some circles. In my view, it may be because it has been used in quite a few substandard projects. In itself, there is nothing wrong with it.

A durable material demands longevity

Overall, both Gottlieb and Wingstrand stress that their interest in bricks does not arise from any perceived “nobility” of the material. ‘Classifying materials as good/bad or dated/contemporary makes, quite simply, no sense to me,’ says Wingstrand.

Both also emphasize the need to work with the material rather than against it: ‘I think that many people – myself included – are attracted to not only the tactile quality of bricks but also their strength and permanence. In a way, bricks make their own demands on the project. A brick wall is not something that you would just pull down again after a few years. The longevity of the building design must be comparable to the durability of the material,’ Gottlieb maintains and goes on to state that Gottlieb Paludan Architects strives to take an unsentimental approach to brickwork:

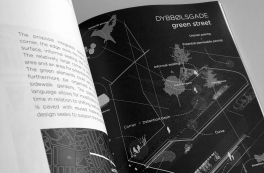

‘We do not idealize artisan products. Machine-made bricks have every justification. The fact is that the joint and the bond are creative devices on a par with the type of brick selected. At Tietgensgade District Cooling Plant, we worked with recessed joints which bring out the individual bricks much more than flush joints would have done. Bear in mind that on large surfaces, even minor artistic effects can have a major impact on the overall appearance. In fact all architectural work consists in administering and orchestrating such design devices.’

Can expansion joints even enrich a façade?

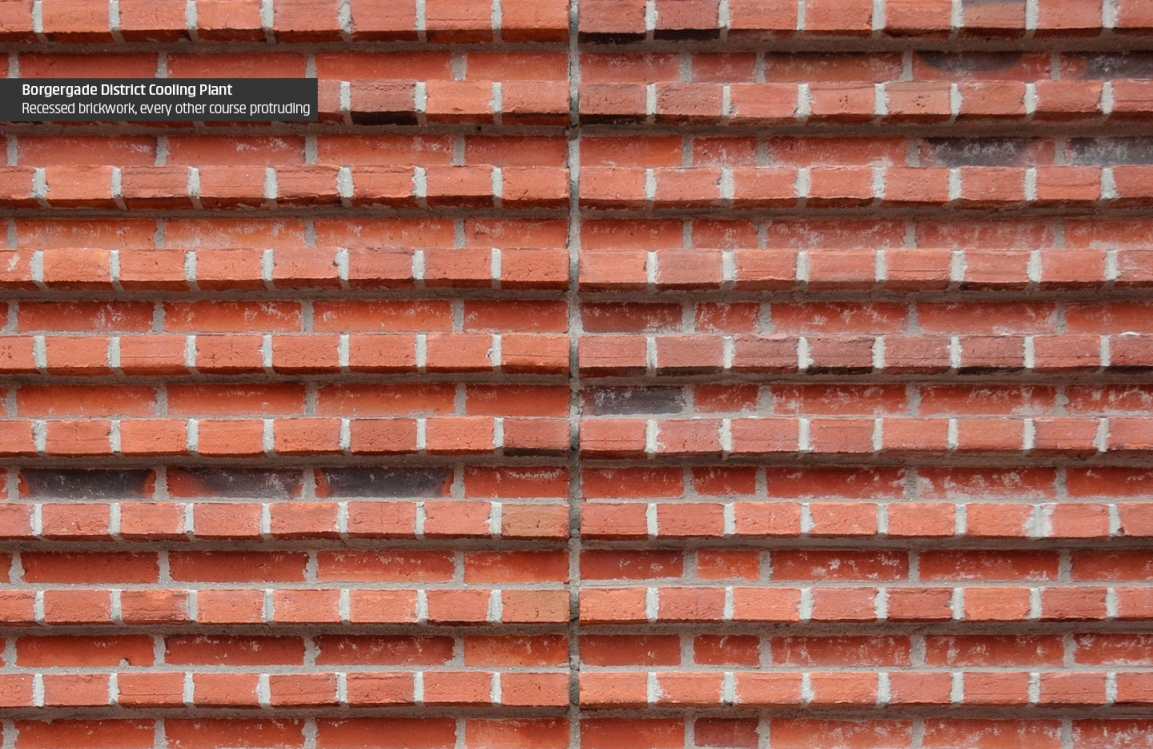

Planning a technical facility at the H.C. Ørsted Power Plant, Gottlieb Paludan Architects was faced with the recurring issue - how to deal with the expansion joints. More often than not, great efforts are made to underplay their presence, unfortunately often resulting in a somewhat strained and less than elegant appearance.

Gottlieb explains: ‘A building such as the substation at the H.C. Ørsted Power Plant is a closed volume. Quite simply, nothing much happens on such a façade. Here, the expansion joints gain importance, because they become the difference that catches your eye. How can they become an enriching focal point in the brickwork? We decided to make a feature of the expansion joints by making them broader and deeper than necessary. In this way, the unsightly rubber joints buried deep in the wall remain hidden. At the same time, we emphasized that it is a non-bearing wall by letting the expansion joint latch on to one of the few openings of the facade. If trying to mimic a solid brick wall, you would avoid this at all costs.

,,

If you want a cohesive city, it is dangerous to leave out the most dominating materials or let them "sand up" without interpreting them afresh

Wingstrand adds: ‘At the H.C. Ørsted Power Plant, we decided on a stretcher bond as our starting point – entirely appropriate for a facing. The bond consists of alternating courses of standard bricks and broad bricks. This creates a protrusion of 60 mm on every alternate course and thereby a shadow effect together with a horizontal, “grooved” ornamentation in the façade. We shifted the bonds along on the corners. It highlights the stacking and produces open, slightly flickering corners. This emphasizes the lightness of the facing. You immediately sense that it is not a solid wall.

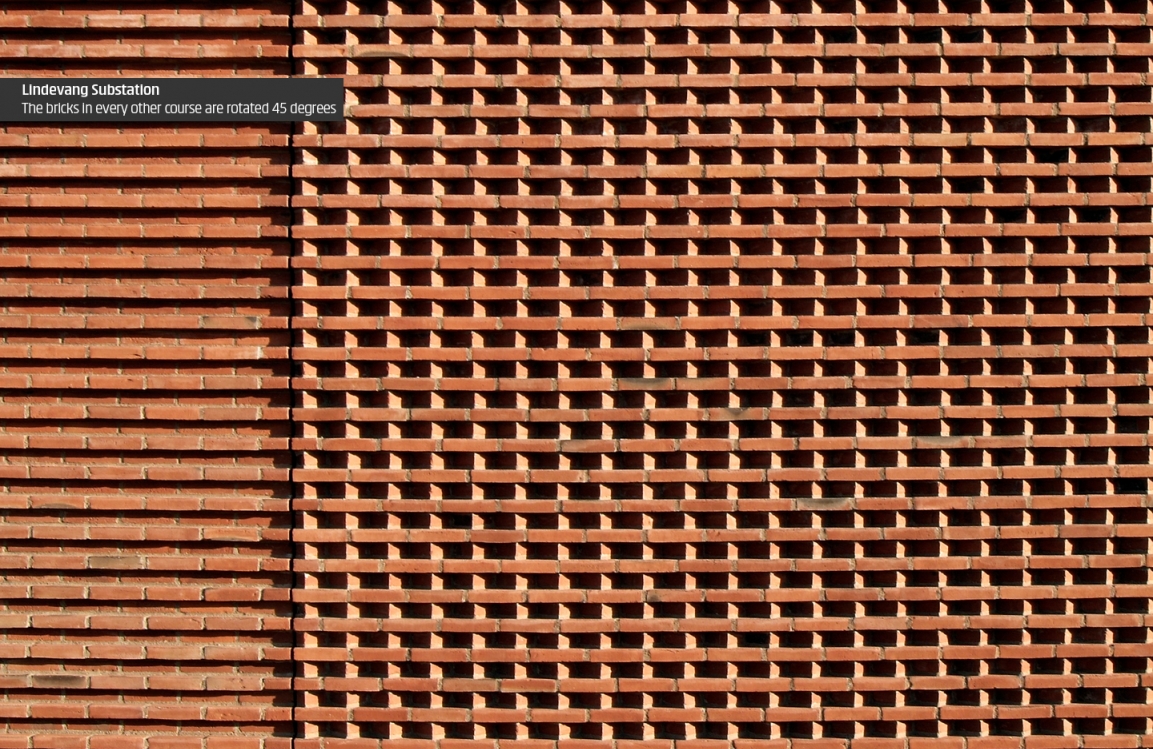

In subsequent projects, such as the Borgergade District Cooling Plant, we also worked with headers in the bond. I think this makes sense specifically for a facing with textured brickwork. Actually, in this way you can build the entire project using just standard bricks. The bricks, turned 90 degrees and displaying their headers, give you exactly the desired protruding courses.’

Who’s afraid of the building code?

‘If you want a cohesive city, it is dangerous to leave out the most dominating materials or let them “sand up” without interpreting them afresh,’ argues Jensen. He highlights the Netherlands, particularly Amsterdam, as a location with brickwork traditions that continue to be strong and vibrant:

‘During the last 10–15 years, there has been a surge in brick constructions, rejuvenating the appearance of brickwork in Amsterdam. In addition the new brick buildings remain closely linked to a long-standing brickwork tradition, not unlike ours in Denmark. Unfortunately, in Denmark, I see no equally strong, collective movement, insisting that bricks have something new to offer as well as contributing to a sense of continuity in the cityscape.’ Jensen goes on to explain that the creative energy of the Dutch movement does not seem to be put off by the country’s building code which is just as strict as ours.

Thus, sharing a particular interest, Gottlieb Paludan Architects has joined forces with Dutch architects Office Winhov on several occasions. They are part of the informal Dutch brickwork cluster and the recently inaugurated building for the Delft City Archives is a result of this collaboration.

A long process is beneficial

Building a utility plant is generally a very long process, because it takes time getting the technical side of things in order. Thus, Gottlieb Paludan Architects often completes a project up to a certain level and then it has to be put aside for a while. Gottlieb argues that this often proves to be a strength: ‘Your deliberations invariably continue at the back of your mind while you have the opportunity to stand back from the project and look at it with fresh eyes.’

,,

Brickwork is not a constructional simplification. After all, it is much easier to stack brick upon brick in a standard stretcher bond. Fundamentally, these projects express an architectural, rather than a narrow constructional, ambition

Wingstrand explains how knowledge and ideas are exchanged on an ongoing basis: ‘The staffing has varied across the brickwork projects, but all of us have been sitting at the same table, geeking out over the technical details,’ he laughs and continues:

‘We discuss, for example, whether textured brickwork works best with stretchers or headers protruding (– stretchers highlight the horizontal lines while headers enhance the play of light and shade in the façade). Also whether the first change should start in or out – we have yet to reach an authoritative conclusion. However, it remains without a doubt that they are important issues to discuss!’

The arrangement of individual parts

In fact, Gottlieb Paludan Architects’ brickwork projects are indicative of the company’s general approach which is to utilize the properties of any material as a creative device. A case in point is the Anhydro Test Centre in Søborg north of Copenhagen. The centre is made up of several volumes, unified by being enveloped in a fine façade of profiled aluminium sheets. The fitting is highlighted as horizontal strips in the façade and the sheets are profiled so they will wrap around round corners of a reasonable radius.

No material will seamlessly “snap” to another. It will give when exposed to changing temperatures and it is subject to wear and tear, fitting techniques and tolerances. The point is to make an artistic quality out of the physical properties that you are dealt by the material in question.

A brick is a finite, independent unit, while brickwork is continuous by nature. As such, a brick wall sums up the task of architecture, namely to arrange individual parts into a whole.

Gottlieb concludes: ‘Textured brickwork is not a constructional simplification. After all, it is much easier to stack brick upon brick in a standard stretcher bond. Fundamentally, these projects express an architectural, rather than a narrow constructional, ambition. We strive to give these additions to existing plants the same architectural value and afford them the same diligence in the design as their predecessors. But with a contemporary ornamentation, please. The cherubs and other historicizing details belong to a time gone by.’

Read about other brick projects: