The essence of sustainability

31.10.2018Christina Tolstrup is Head of Sustainability Design at Gottlieb Paludan Architects. She was instrumental in developing a number of high-profile projects focusing on sustainability, such as Køge Waterworks and the Climate and Environmental Centre in Hillerød.

In this interview, Christina Tolstrup elaborates on how we contribute to the advancement of sustainability in our own projects and in collaborations with our developers, contractors and other stakeholders.

How do we include sustainability in our design process?

We have a clear procedure for screening every project for its sustainability potential. This may include SUDS solutions, reduction of the power consumption and green roofs. In other words, it is crucial to include sustainability assessments in the preliminary phases to establish a project’s potential. We describe these sustainability features to the client and explain the design and the financial implications, if the client decides to have the project certified. Our screening method was devised with inspiration from the DGNB certification system, because this is the system that is generally used in Denmark and because the DGNB system is also comparable to other European standards. For our projects, we use a simple screening list, as we decided that it would be an advantage to produce a list that could be used by everybody – irrespective of knowledge, training and experience – in order to ensure that all projects are screened.

A case in point is, for example, the Climate and Environmental Centre in the North Zealand town of Hillerød: it is a project that was screened for its sustainability potential and it lives up to a large number of the environmental requirements that are included in the large DGNB list. For this project, we operated with ‘ten commandments’ by which we mean ten basic principles that originate from the large list. They were all principles which, based on our professional knowledge and experience, would be possible to implement, taking into account the budget of the project and the client’s ambition. The features included optimizing daylight, combining natural and mechanical ventilation, fitting solar panels on the top roof to produce power, creating green roofs on the roofs that are visible from inside the building and SUDS solutions. All these features were implemented in the final project together with an exit strategy which meant that the building was constructed in such a way that it may be disassembled in recyclable sections at the end of the building’s service life, which was why we prioritized ‘raw’ materials and minimized the use of surface treatments, pointing, etc. In addition, a number of social sustainability initiatives were implemented; for example, the integration between functions, different groups of professionals and internal/external users was given priority when deciding the layout of the building. The master plan for the area also addresses social and environmental sustainability. The project illustrates beautifully how many of society’s basic functions may be highlighted, without negatively impacting the landscape or the environment.

Our CHP plants and other technical installations do not have longer service lives than the equipment they house. This means that it makes perfect sense to use the ‘design to disassembly’ method. For the Swedish CHP plant Värtaverket, for instance, we designed solutions which ensure that individual parts may be replaced, for example by using screws instead of nails. Such initiatives extend the permanence of the buildings, as they may be adapted to the processing plant as and when required.

,,

We have a clear procedure for screening every projectfor its sustainability potential.

How do you use the ‘ten commandments’ and what are the benefits compared to the large DGNB list?

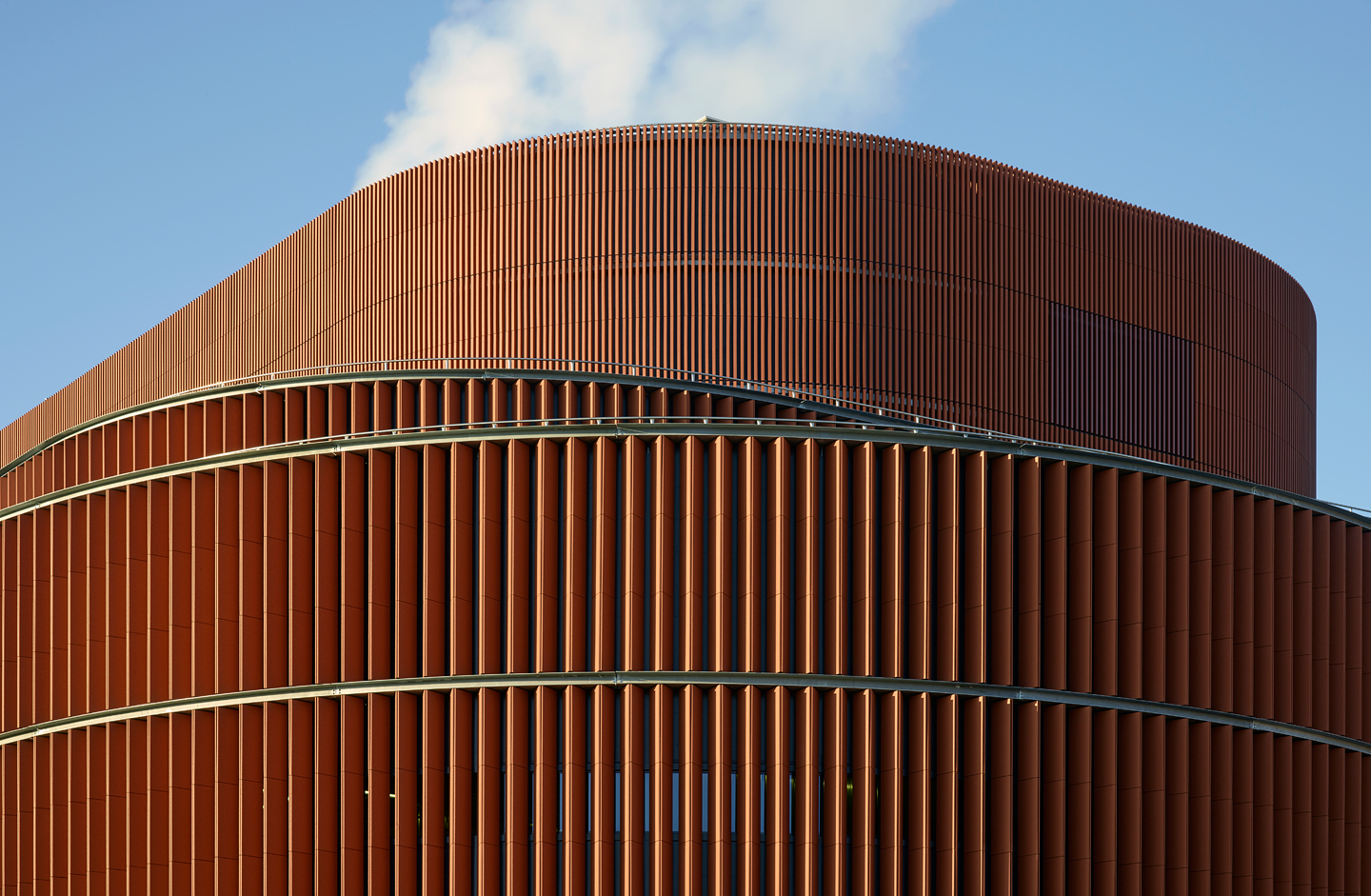

The ‘ten commandments’ is a good method, because we can highlight some important points for the client and make it more manageable to implement sustainable parameters. It is a way in which we can ensure implementation of all four DGNB parameters: financial, environmental, social and technical qualities in our projects. By devising the ‘ten commandments’, we are also able to ensure that it is the parameters that make sense in connection with the individual project that are included. The large DGNB list can appear somewhat rigid and ‘overholistic’, as it may not necessarily make sense to include social sustainability in connection with a large technical plant. There are also projects where the environment is of the very highest priority, and we do everything we can to source the best sustainable materials. A case in point in this respect is BIO4, a huge woodchip-fired CHP unit at Amagerværket in Copenhagen. The CHP unit will be enclosed by a deep façade made up by suspended tree trunks which may be burnt inside the incineration plant, if one day the installation is to be demolished or refashioned. BIO4 will become not only a striking tale of wood as fuel but also a symbol of Copenhagen’s ambition to become the world’s first CO2-neutral capital by 2025. Such a project incorporates various environmental sustainable initiatives, and it may easily be argued that it also has social qualities, as the building itself explains what goes on inside, both because the tree trunks tell their own story and because a long staircase along the façade enables visitors to get close to the building and see the technical installations through the windows. On the other hand, BIO4 is not particularly financially sustainable, as it is after all not necessary in order for the plant to operate.

,,

By devising the 'ten commandments', we are also able to ensure that it is the parameters that make sense in connetion with the individual project that are included.

With the ‘ten commandments’, we use the DGNB system to pick the points that make sense. This means, of course, that the projects cannot be DGNB-certified, but we do ensure that the areas that make most sense are reviewed and included. In addition, there are after all other certification schemes than DGNB, and we are currently working on a number of projects with data centres that are certified according to the US and British standards, LEED and BREEAM. These projects have foreign clients and for them, it may be of more value that their projects are certified according to standards with which they are familiar. For us, the certification is not important in itself; the most important thing is to find measurable solutions that optimize the sustainability of the projects and to constantly ask ourselves the question: Can this be done better?